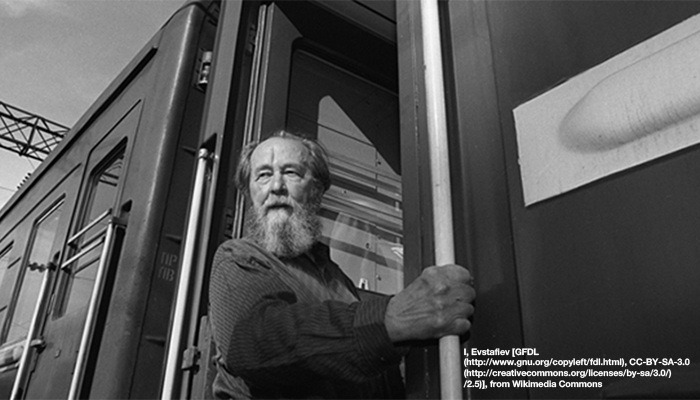

Commemoration of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

2 Timothy 1:3-10 | Sermon for commemoration of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Proclaimed on 3 August 2018 at Australian Lutheran College chapel by Pastor Tom Pietsch

Introduction

On this exact day ten years ago, towards evening, one of the most courageous Christians of the twentieth century died from heart failure on the outskirts of Moscow.

His name was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and his death was followed by tributes from world leaders, including from some whose countries had formerly spurned Solzhenitsyn.

As we thank God for the faith of his saints, and as the Spirit leads us to imitate their faith, I just want to recount some of the details of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn’s life to you.

Life

He was born 100 years ago and raised in Russia to be a Marxist supporter of the Revolution who despised religion. This philosophy held until a phenomenal run of tragedy led him deeper into life.

In the Second World War, fighting on the Russian front he was captured by Germans and put in a POW camp. The conditions were especially atrocious because of the German animosity to Russians at the time. Upon his release however, Solzhenitsyn was tried in Russia for being a dissident because in a private letter he had referred to Stalin as “the boss”, a mildly derogatory comment. For this he was sentenced to eight years in the Gulags in Siberia.

It’s estimated that the Gulags killed around 60 million people between 1919 and 1959, which is around 10 times as many as Hitler’s genocide. The courage of the man began to show as he witnessed first the horrific war crimes of both Russians and Germans, and then the evil and dehumanizing forces in the Gulags. He later wrote that he began to ask himself the question “Was I any better than these men?”

At the end of his Gulag sentence, Solzhenitsyn then contracted cancer that was deemed terminal. In the hospital he one night spoke with his doctor who told him of his conversion from Judaism to Christianity. He told Solzhenitsyn that every punishment that we suffer is deserved by a transgression we’ve committed. Solzhenitsyn went to bed thinking about that, and woke to the news that the doctor had been beaten to death during the night. Solzhenitsyn kept on thinking about punishment as just deserts, but grew to see how ludicrous it was – then Stalin would have been less evil than the millions he’d slaughtered. He later wrote, in his momentous book The Gulag Archipelago:

The only solution to this would be that the meaning of earthly existence lies not, as we have grown used to thinking, in prospering, but… in the development of the soul. From that point of view our torturers have been punished most horribly of all: they are turning into swine, they are departing downward from humanity. From that point of view punishment is inflicted on those whose development holds out hope.

It was through suffering and the cross that Solzhenitsyn came to Christ. Or better, as he put it in his poetry, “I renounced You, but You stood by me”.

He renounced his atheist Marxism and came to look on his own soul with a courageous honesty and humility that only Christ come give. Again, in the Gulag Archipelago he wrote,

In the intoxication of youthful successes I had felt myself to be infallible, and I was therefore cruel. In the surfeit of power I was a murderer and an oppressor. In my most evil moments I was convinced that I was doing good, and I was well supplied with systematic arguments. It was only when I lay there on rotting prison straw that I sensed within myself the first stirrings of good. Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts…. That is why I turn back to the years of my imprisonment and say, sometimes to the astonishment of those about me: “Bless you, prison!” I…have served enough time there. I nourished my soul there, and I say without hesitation: “Bless you, prison, for having been in my life!” (The Gulag Archipelago: 1918-1956, Vol. 2, 615-617)

Political

Upon release, Solzhenitsyn published a string of books which included his most famous work, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Through these works, the tyranny of Marxism was revealed and the murderous Soviet Regime was exposed for the world to see. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the Templeton Prize, and accolades the world over. The KGB tried to poison him in 1971 and while he survived, only a few years later he was expelled from Russia altogether.

The USA especially gave him a huge welcome as a whistle-blower on the corruption of the Soviet Union, who had suffered for his courage truth-telling. He was even invited to give the commencement address at Harvard University where record numbers came to hear him speak. They were all in for a shock.

Solzhenitsyn took the stage to warn Americans of the toxicity of their own culture. Here are some highlights:

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature which an outside observer notices in the West in our days. The Western world has lost its civil courage.

Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society appears to have little defense against the abyss of human decadence, such as, for example, misuse of liberty for moral violence against young people, such as motion pictures full of pornography, crime, and horror. It is considered to be part of freedom and theoretically counterbalanced by the young people’s right not to look or not to accept. Life organized legalistically has thus shown its inability to defend itself against the corrosion of evil.

No, I could not recommend your society in its present state as an ideal for the transformation of ours. Through intense suffering our country has now achieved a spiritual development of such intensity that the Western system in its present state of spiritual exhaustion does not look attractive… After the suffering of decades of violence and oppression, the human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer than those offered by today’s mass living habits, introduced as by a calling card by the revolting invasion of commercial advertising, by TV stupor, and by intolerable music.

As the speech began to sink in, audible boos started to be heard and members of the audience started walking out. One commentator put it this way: “It was as if an Old Testament prophet had been invited by mistake to be guest of honor at the banquet of a profligate prince, and instead of thanking his host and flattering the assembled party-goers rose up and told them they were going to Hell.”

Having alienated both communists and capitalists, Solzhenitsyn continued to be a sign of contradiction, a witness to the spiritual life of humankind, against the violence and banality of modern and Soviet life. Through the mercy and eternal security of the Gospel, God gave Solzhenitsyn not a spirit of fear but of power and love and self-control.

No matter who his audience was, Solzhenitsyn is an example to us of not being ashamed of the testimony about our Lord, willing to share in suffering for the Gospel by the power of God, not because of our works, but because of his own purpose and grace, which he gave us in Christ Jesus before the ages began.

Following the Soviet Union’s dissolution, he returned to Russia in 1994 and yet remained something of a permanent spiritual exile, with no lasting city but the heavenly Jerusalem.

Conclusion

Perhaps the one lesson that history must learn from the twentieth century is that “the line separating good and evil is drawn through the human heart.” Or perhaps it is that “the human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer than those offered by today’s mass living habits”. Either way, it will only be by Christ’s Gospel working courage in people like Solzhenitsyn that history will learn anything at all.

And may the peace of God that passes all understanding keep your hearts and minds safe in Christ Jesus our Lord. Amen.